TestPage

December 1, 2017

Introduction

Common Semitic Roots

Arabic and Hebrew are certainly two distinct, mutually unintelligible languages. However, it will be immediately apparent to one who studies even a little of each that they do share grammatical similarities of many kinds, including each having many words that are similar in both sound and meaning to corresponding words in the other language. Many of these lexical correspondences can be traced back to several historical periods in which Hebrew borrowed words from Arabic. A small number likely originated as Hebrew loanwords that entered Arabic (possibly via Aramaic) in the centuries that led up to the revelation of the Qur’an. But going back even further, into the most remote ancient linguistic strata of both languages, before any borrowings between them had taken place, there can already be found many words that, but for minor differences in pronunciation, are exactly the same in both languages. This is due to the fact that both Arabic and Hebrew are members of the Semitic family of languages. The ancient words they share in common are primitive linguistic survivals in the two tongues from a period before they had split apart. These words go back to a time in which Semitic peoples were speaking different dialects of Proto-Semitic, the name that scholars have given the ancient language from which all Semitic languages originate, its lexicon describing the daily life of the inhabitants of the Middle East of more than 7000 years ago.

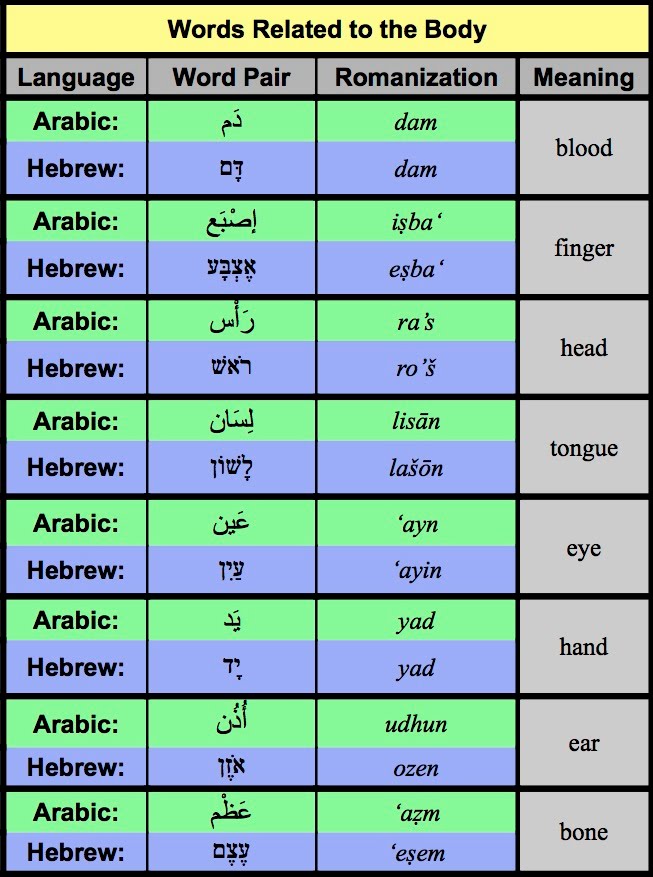

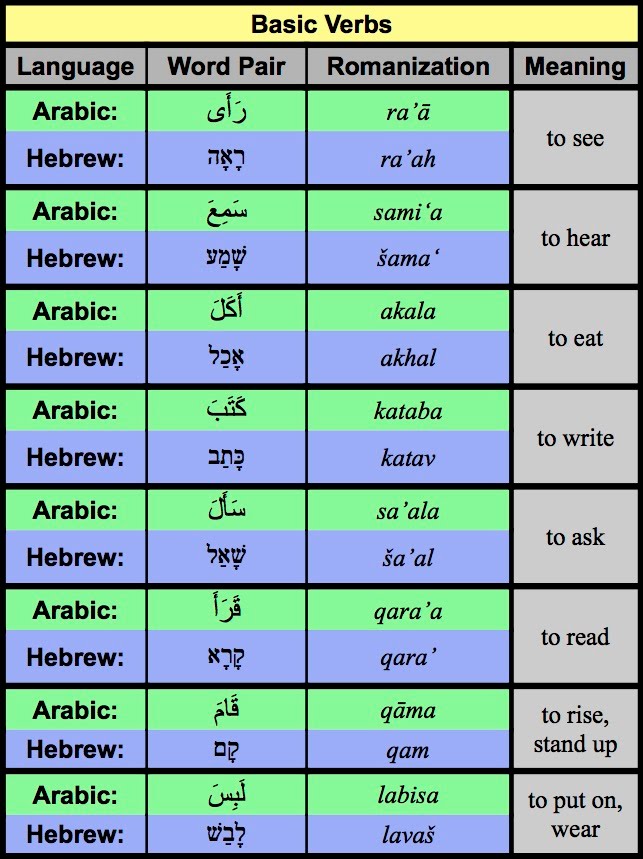

In tables 1 to 6 below are listed a selection of related Arabic and Hebrew words which appear in the most ancient written records of each language. Forms similar to these occur in the earliest examples of other Semitic tongues as well, such as those of ancient Ethiopia (Ge’ez), Mesopotamia (Akkadian), and Phoenicia (Phoenician, Punic).

Table 1

Table 2

Table 3

Table 4

Table 5**

Table 6

As can be seen in the tables above, there was a time when the two languages might have been understood as being merely different dialects of a single tongue. However, linguistic change being inevitable, this state would not last. By the time Hebrew and Arabic would emerge from Proto-Semitic as separate languages, many previously identical words had diverged considerably in pronunciation, in many cases beyond the point of mutual intelligibility, as will be seen in the next section.

Pronunciation Changes

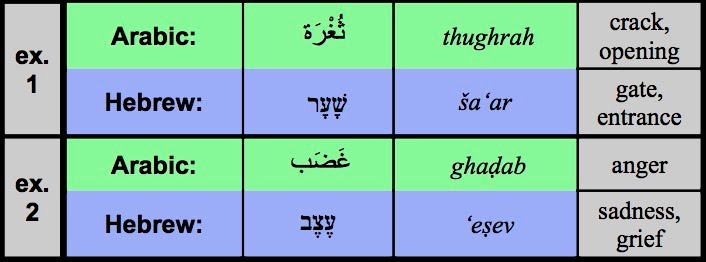

As pronunciation changes developed in the two dialects of Proto-Semitic that diverged to eventually become Arabic and Hebrew, Arabic and Hebrew word pairs arose whose common origins are not so apparent. Below are two (rather extreme) examples illustrating this development:

Table 7

Despite their differing outward forms, for each example to the right there is a single Proto-Semitic word from which both the Arabic and Hebrew words have descended. In the first, it would have been a word denoting a type of opening; in the second, a negative emotion. The words’ meanings have diverged somewhat, and even more so have the sounds of the words, so that the original one-to-one root letter correspondence between the pairs of words in each example is at this point invisible. If however one understands the predictable way in which Semitic sounds have changed over time, one can recognize each pair as having root letters that were originally exactly the same.

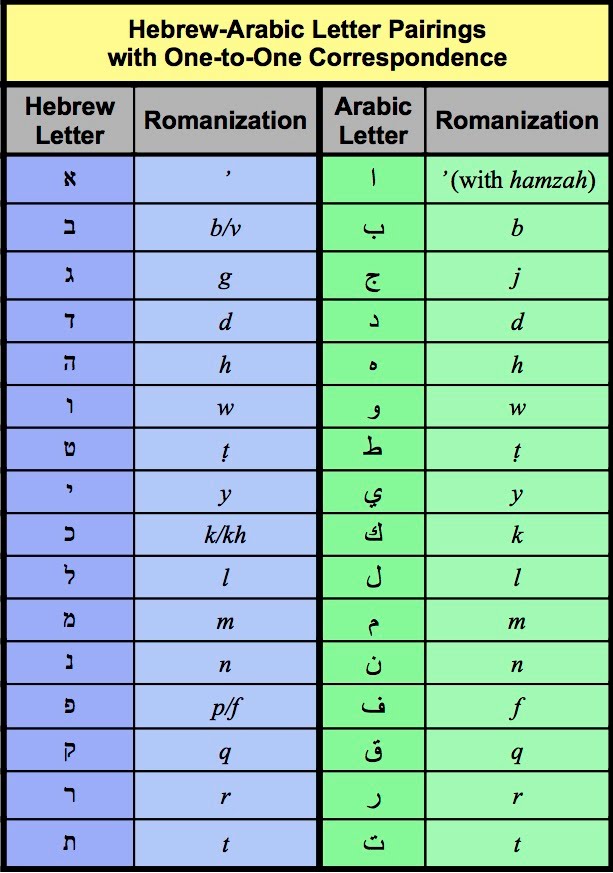

Most letters of the Hebrew alphabet are related to letters of the Arabic alphabet in a one-to-one predictable correspondence, having exact counterparts in the other language that, for the most part, represent the exact same sounds. These (they amount to a total of 16 letters pairings out of the 22-letter Hebrew and 28-letter Arabic alphabets) are given in the table below:

Table 8

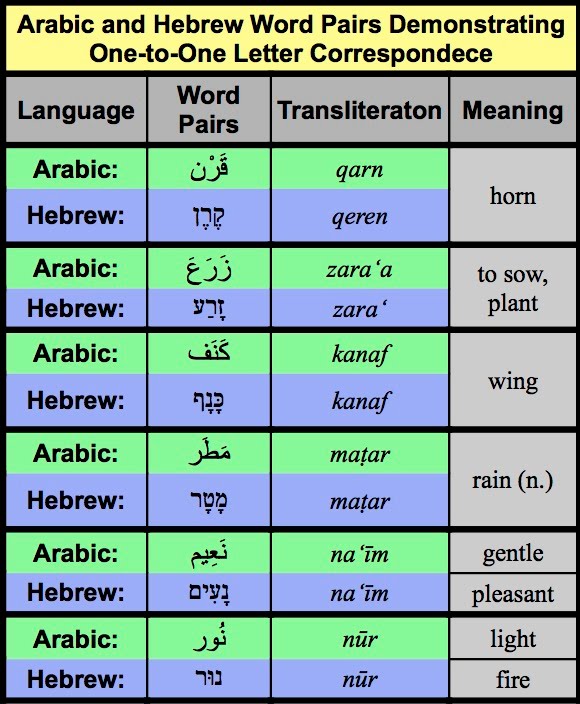

Below are a few examples of words that use only these letters. Because they limit themselves to using only these letters, the words in each pair below are extremely similar or identical:

Table 9

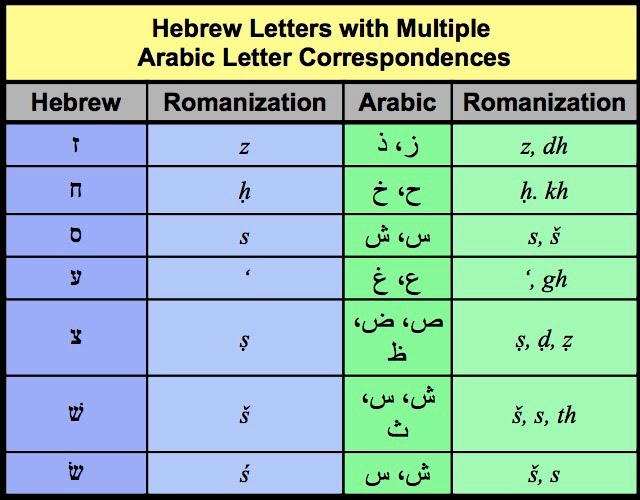

But there are other Hebrew letters that correspond to not one but to two or even three different letters of the Arabic alphabet, and it is this type of relation that is the cause of most of the seeming dissimilarity in the word pairs noted at the top of this page, in Table

- These letters are listed in the table below.

Table 10

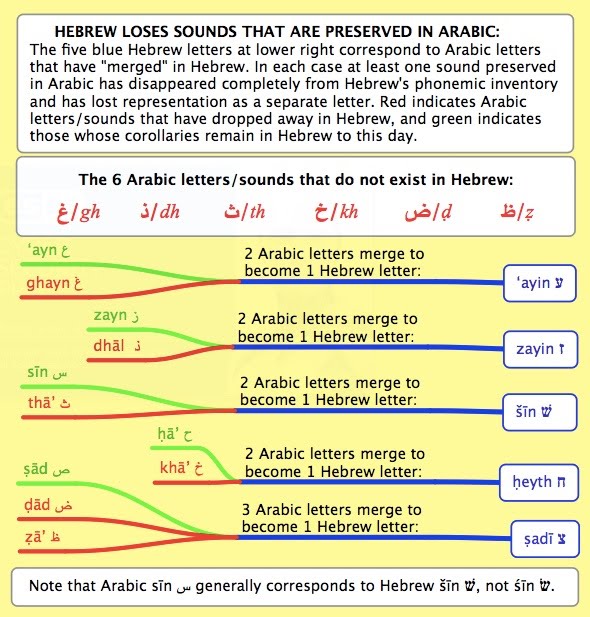

Most of the multiple correspondences outlined above originate in phonetic changes that arose in formative stages of what would become Arabic and Hebrew. (Some of the correspondences among the sibilants, or ‘s’ and ‘sh’ sounds, are an exception – see below). First, speakers of what would become Hebrew began to no longer differentiate in their speech between certain previously distinct Semitic sounds. Sounds that Arabic would retain until the present day, represented by the letters

ث th, خ kh, ذ dh, غ gh, ض ḍ, and ظ ẓ,

would completely disappear in Hebrew pronunciation, and instead merge with the sounds represented by the already present Hebrew letters

שׁ š, ח ḥ, ז z, ע ‘, and צ ṣ, respectively.

(See here and here for proof that at least some of these changes were quite late, with distinctions between the merged sounds still pronounced at the time of the translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek.)

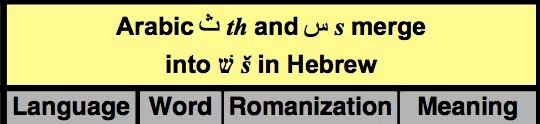

Separately, changes occurred that caused sibilants to “trade places” between Arabic and Hebrew. One can thus find many word pairs of similar meaning where the Arabic word contains a ش š, whereas its Hebrew counterpart contains a שׂ ś. Alternately, where Arabic س s is found, a parallel Hebrew word will often display a שׁ š. Sometimes the Hebrew counterpart of س s will instead be ס s, a Hebrew letter not existing in Arabic, today pronounced exactly the same as שׂ ś, all three of which sounding just like the English letter ‘s’. Other correspondences among the letters representing sibilants can be found as well, but these originate in later loan-words, or in confusions within Hebrew between the homophones ס s and שׂ ś.

A visual summary of the main points covered above is provided below:

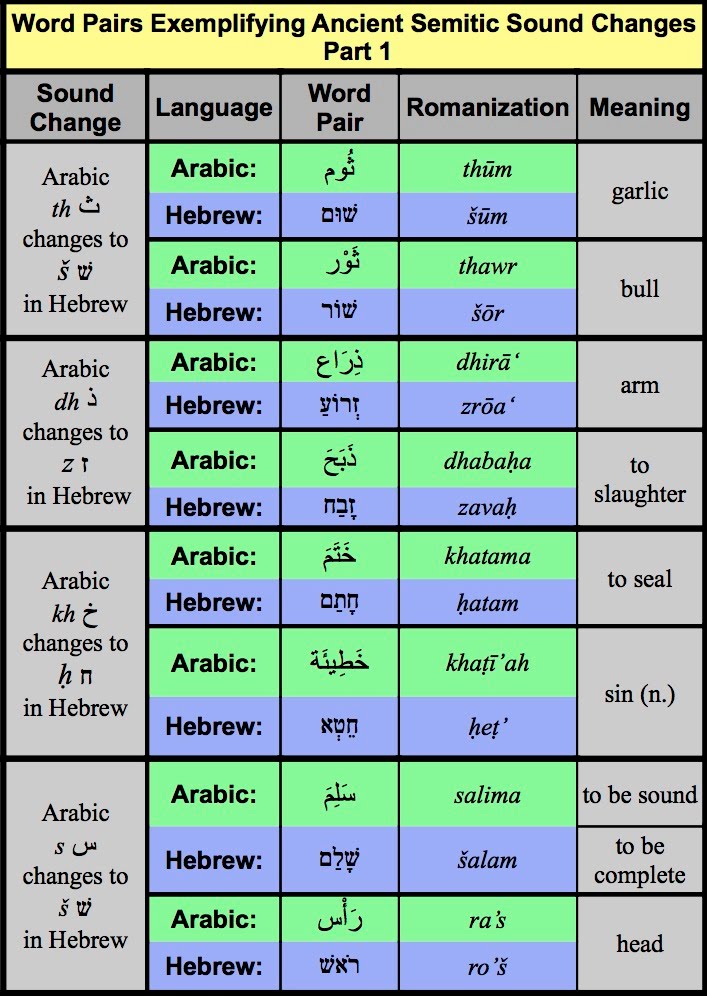

The word pairs in the following two tables illustrate the sound changes discussed thus far. Two words are provided as examples for each sound change.

Table 11

Table 12

In accordance with the decrease in Hebrew’s inventory of sounds, Hebrew’s alphabet has less letters than that of Arabic—Arabic’s alphabet possessing 28 letters and that of Hebrew only 22.

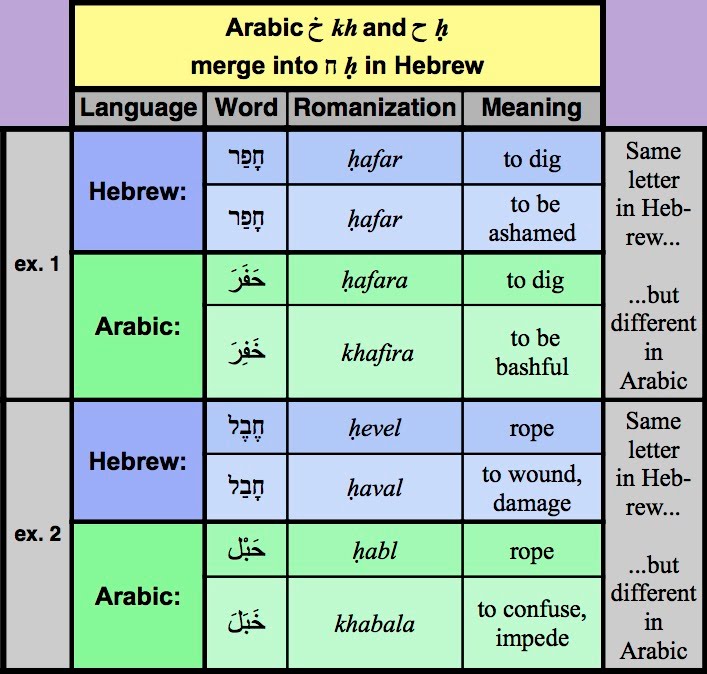

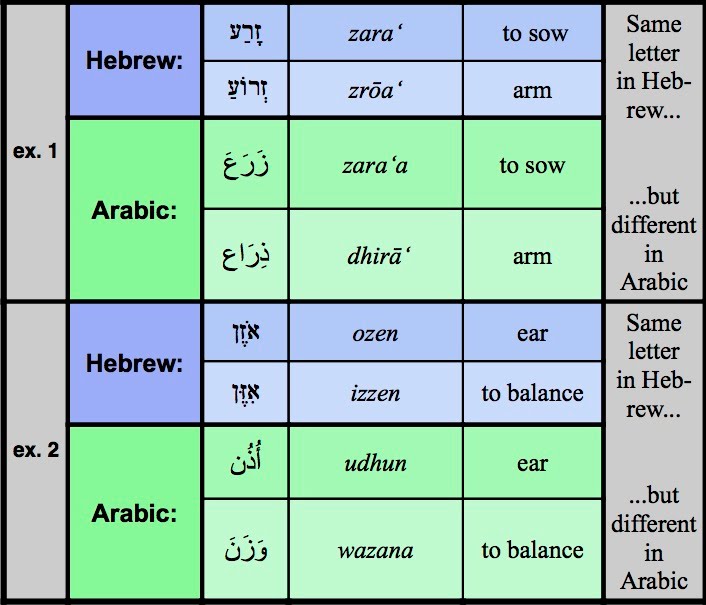

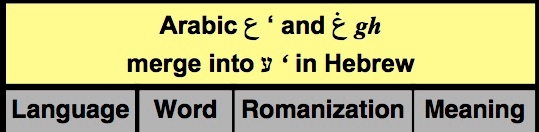

Hebrew’s loss of differentiation between certain sounds is also associated with the arising of pairs of Hebrew words (and in one instance - that of ex. 4 in Table 17, below - a group of three words) that appear to be of the same root, but which have curiously unrelated meanings. Comparison of these near (or actual) homonyms with corresponding Arabic words reveals that they can be traced back to originally completely separate Semitic roots that merged in Hebrew in ancient times due to its inability to distinguish them in pronunciation.

For example, خ kh and ح ḥ, remaining separate in Arabic, would both come to be pronounced in Hebrew as ח ḥ:

Table 13

Arabic ذ dh and ز z would both come to be pronounced as ז z in Hebrew:

Table 14

Arabic ث th and س s would both come to be pronounced as שׁ š in Hebrew:

Table 15

ع ‘ and غ gh would both merge to become the Hebrew letter ע ‘ :

Table 16

and ظ ẓ, ض ḍ, and ص ṣ would all three come to merge in the single Hebrew letter צ ṣ:

**Table 17

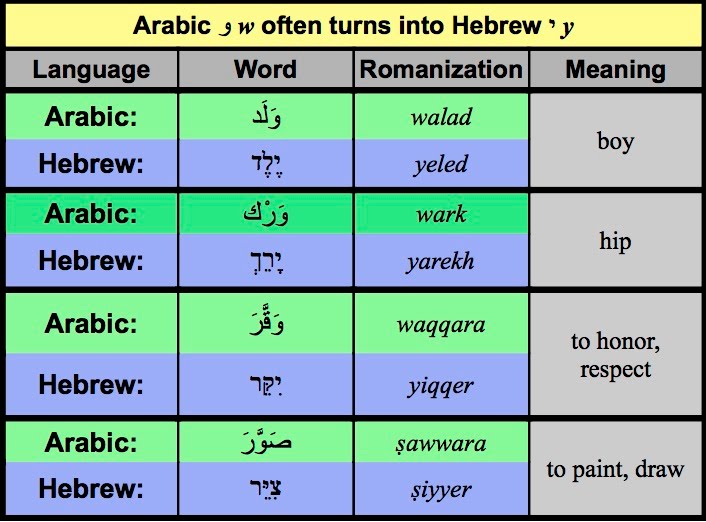

Another change that we may observe as Hebrew developed from Proto-Semitic is the tendency for the sound represented in Arabic by و w to often manifest as י y in Hebrew. Some examples:

Table 18

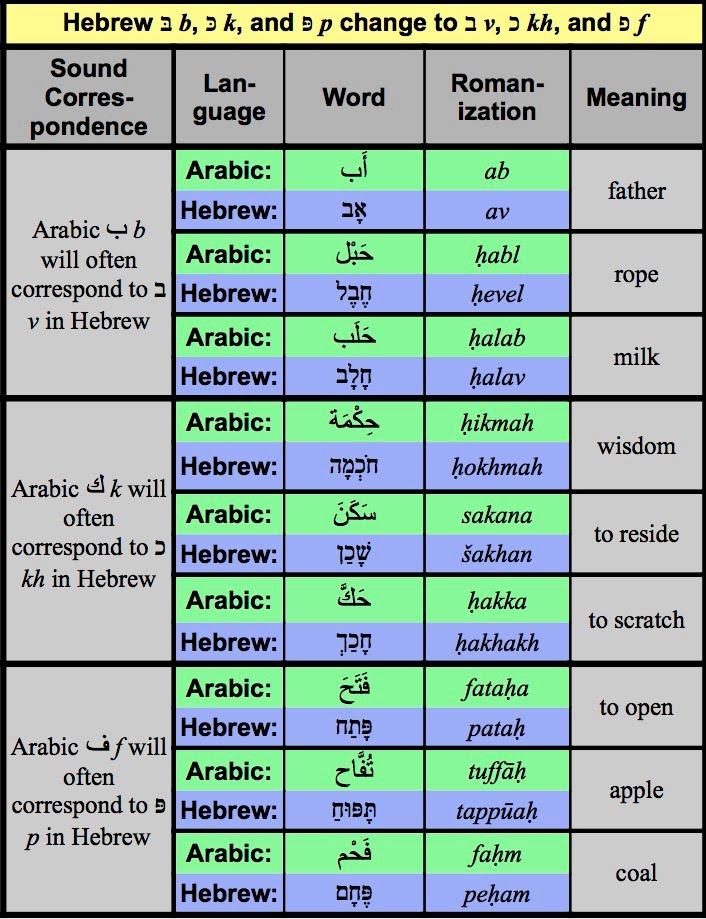

The changes did not stop there. Another development in Hebrew pronunciation was the transformation of the sounds represented by the letters בּ b, גּ g, דּ d, כּ k, פּ p, and תּ t. Depending upon where they occur within a word, they would come to be pronounced as “softer” versions of themselves: ב v, ג gh, ד dh, כ kh, פ f, and ת th. This would have the effect of distancing the sound of Hebrew now slightly even further from her sister language Arabic. (An exception exists in the case of the Hebrew letter פּ p. Hebrew פּ p corresponds to Arabic ف f, so in a word where פּ p turns into פ f, this actually makes it closer to its Arabic counterpart). In contemporary spoken Hebrew three of the six softer variants have dropped away, but distinctions do continue to exist for בּ/ב b/v, כּ/כ k/kh, and פּ/פ p/f, as shown in Table 19 below, which provides three examples for each sound change.

Table 19

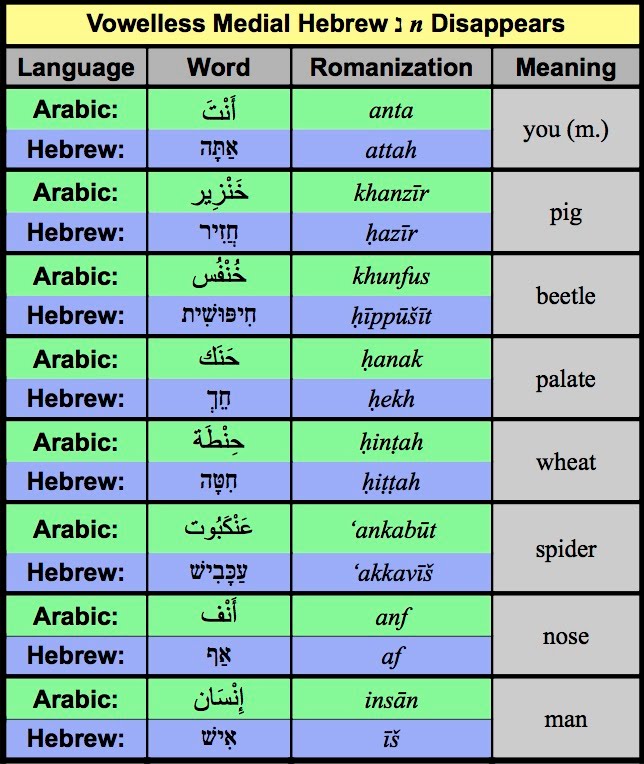

Lastly, notice the pairs below, in which the Arabic letter ن n is present in the Arabic word, but in which the Hebrew letter נ n, its corollary, is mysteriously absent in the Hebrew word. This is because at some point before Hebrew was ever written down, its speakers ceased to pronounce the sound represented by the letter נ n when נ n occurred in the middle of a word without a vowel following it. Under these conditions the sound represented by Hebrew נ n would become silent. The Arabic letter ن n would, however, continue to be pronounced in Arabic under these conditions, and is thus present in each Arabic word in the table below.

Table 20

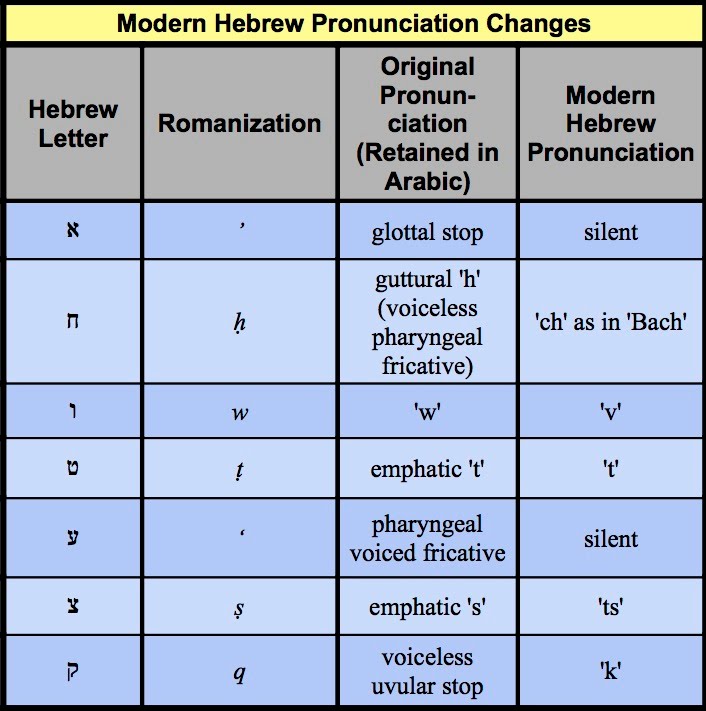

To conclude our discussion of the development of differences in pronunciation between Hebrew and Arabic, we move forward to modern times, in which we can observe a phenomenon that began in the late 19th century. As the dominant pronunciation system of contemporary Hebrew originated in the speech patterns of people whose mother tongues were not Semitic, many found difficuty in producing the unique sounds characteristic of Semitic languages. Because of this, the following Hebrew pronunciations, not reflected in writing, are common today. Hebrew, at least in its spoken form, was in this way further differentiated from Arabic, which itself never lost the original pronunciations listed in Table 21, below.

Table 21

Hebrew Loan-Words in the Qur’an

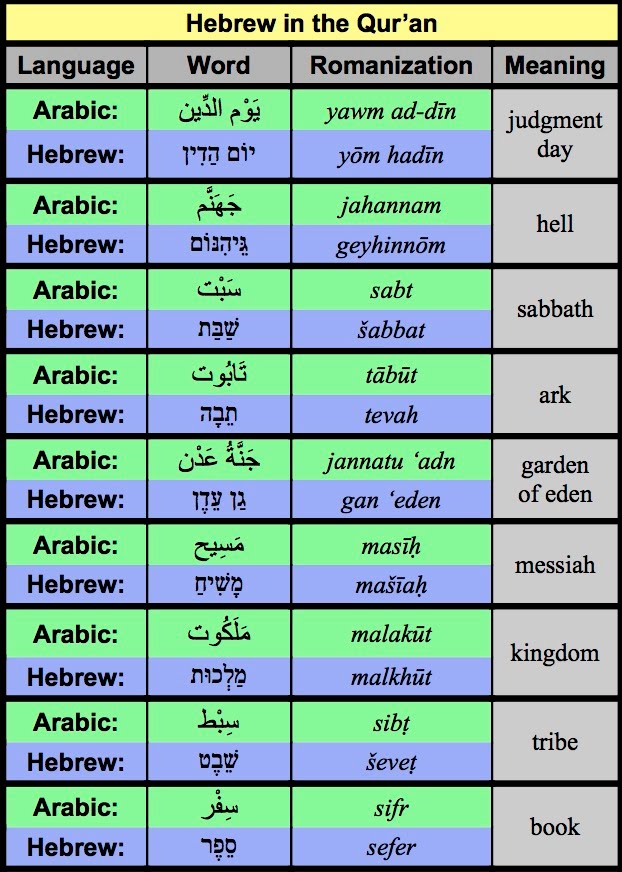

Once Proto-Semitic had split into separate languages, due, in part, to changes such as those described in the previous section, those languages would naturally begin to borrow words from one another as the populations, religions, and civilizations employing them interacted historically. The details surrounding the issue of Hebrew loan-words entering Arabic in the centuries leading up to the revelation of the Qur’an are as obscure as they are controversial (at least to some among orthodox Muslims, who base their objections upon a literal reading of the Qur’an’s description of itself as having been revealed in ‘pure Arabic’), but it is a fact that the religious terminology of monotheism as found in Islam’s holy book includes a number of words that bear striking similarity to words of Hebrew origin that had already been in use for as long as a millennium. At the time of the rise of Islam, Aramaic speaking adherents of both Rabbinic Judaism and Near Eastern Christianity were living in the midst of the pagan culture of Arabia, influencing the milieu into which the prophet Muhammad and the scripture he revealed, the Qur’an, were born. Both Jews and Christians had already been using Hebrew’s Northwest Semitic sister language Aramaic as either a mother tongue, a religious language, and/or as a lingua franca for hundreds of years. Because Arabic, Hebrew, and Aramaic are all related Semitic languages it is sometimes difficult to discern the ultimate origin of a given Qur’anic word that displays possible Hebrew origins, but scholars (including a number of medieval Muslim scholars and linguists) generally assert that Hebrew words, in either their original forms or in Aramaic formulations, do appear within the Arabic text of the Qur’an.

Some examples follow:

Table 22

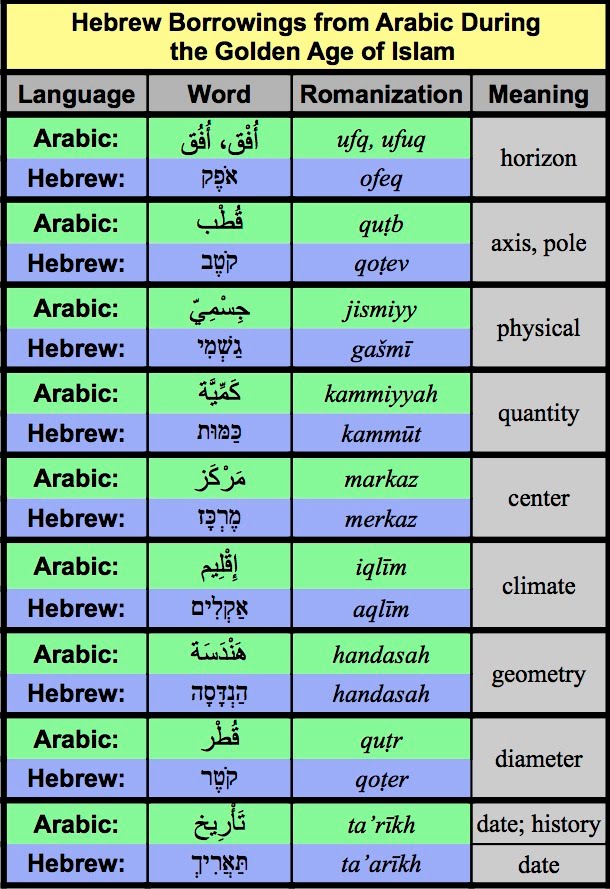

Borrowings During the Golden Age of Islam

Over the centuries of Islams expansion, Arabic would become the language of literature, poetry, science, law, and scholarly discourse in Islamic realms that stretched from North Africa to Central Asia. Jews living under Islamic rule would participate in what would become known as the golden age of Islam, extending from the 8th to the 13th centuries. Works in many languages, including those originating in the Graeco-Roman world were collected and translated into Arabic, from which further translations into other languages, including Hebrew, were made. At this point, not having been spoken as a vernacular for a thousand years, Hebrew was found by Jewish translators to be lacking in vocabulary able to describe the new philosophical and scientific concepts circulating in such an advanced cosmopolitan civilization. As they translated works into Hebrew and produced their own original Hebrew texts, Jews living under Islamic dominion borrowed Arabic technical terms to refer to things for which their ancient scriptural tongue had words.

Some of these are presented in the following table:

Table 23

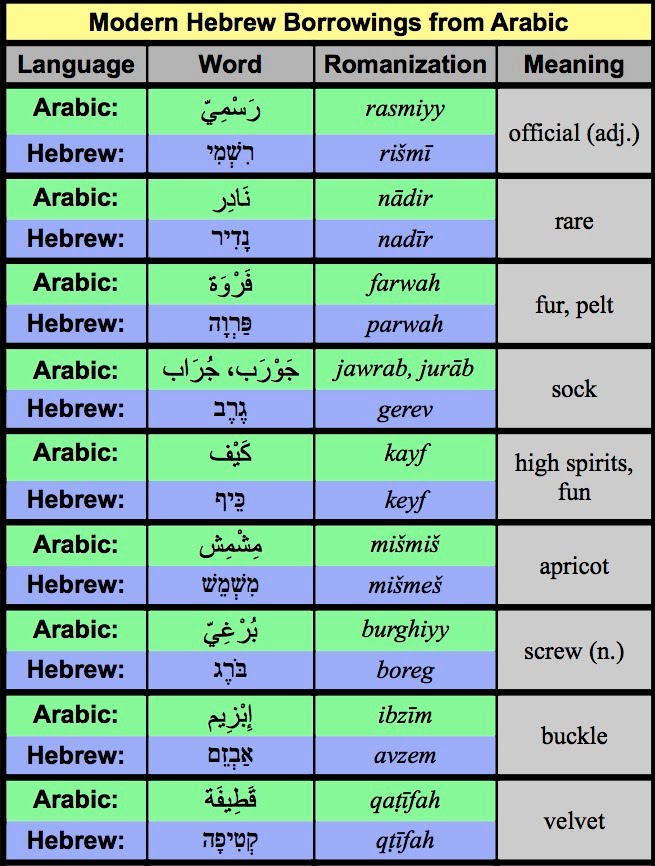

Modern Borrowings

In the late 19th and early 20th century, Zionists, wishing to revive Hebrew as a literary and spoken language, began to borrow from foreign languages in order to expand the Hebrew lexicon beyond the expressive limits of the corpus of ancient and medieval Hebrew. Despite the expansion of vocabulary it had experienced during the Islamic golden age, Hebrew found itself again unable to keep up with the world around it, this time requiring many new terms related to everyday life in the modern industrial age. They used ancient Hebrew sources to create many neologisms, and borrowed many words from European languages, but they also once again chose the language of the Arabs as a natural fount for the importation of many new words, particularly those for concrete everyday objects and items. Finally, in the mid-20th century, with the immigration of hundreds of thousands of Arabic speaking Jews to Israel, as well as through daily interaction between speakers of the new Hebrew and the Arabic speaking inhabitants of Palestine and Israel, Arabic words would naturally enter into the Hebrew lexicon.

Some examples follow:

Table 24

Reference Charts

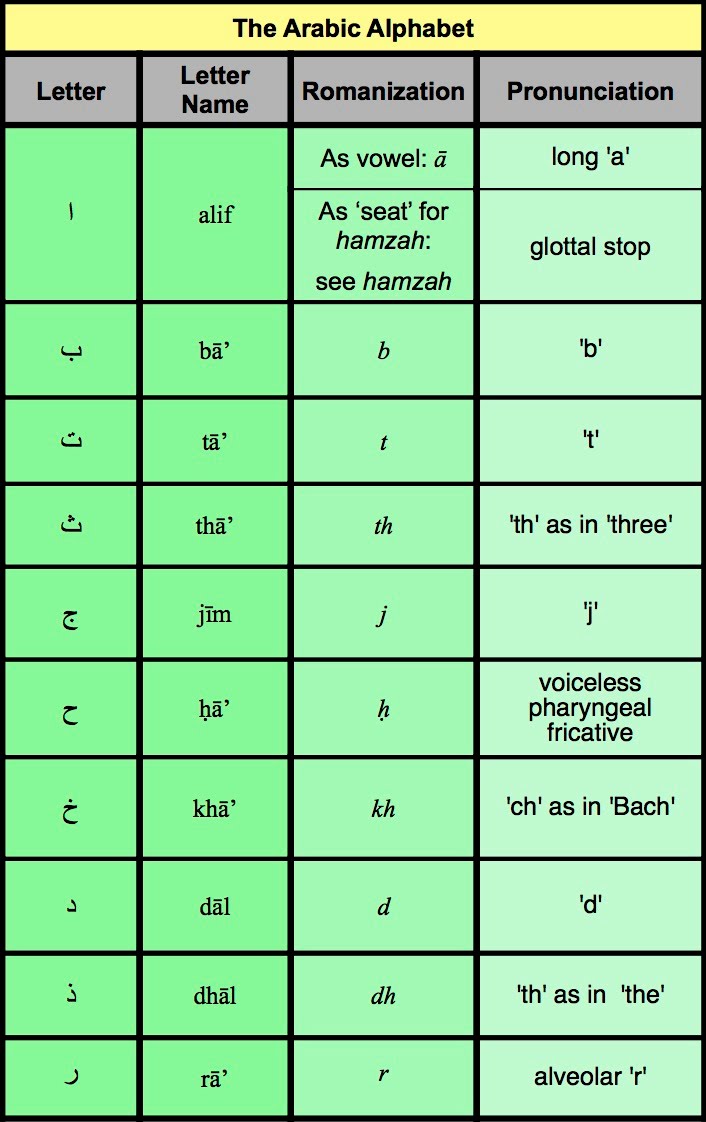

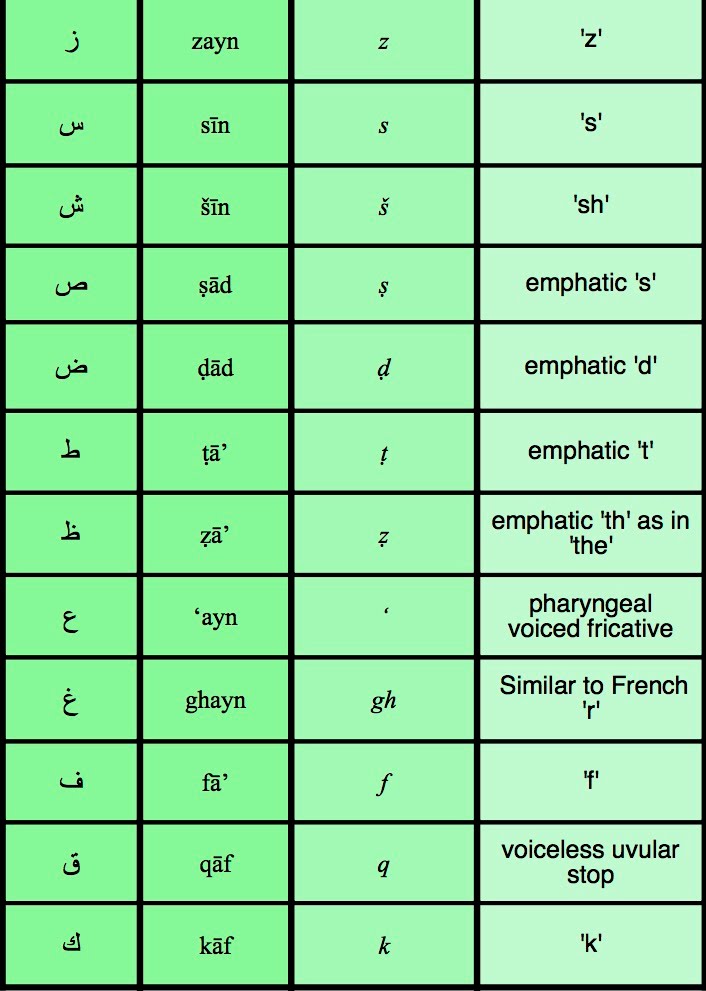

The Arabic Alphabet

Table 25

Note on Arabic Romanization:** Arabic has been romanized so as to

correspond to its written classical form, fuṣhā (‘clear’ or ‘eloquent’ Arabic), and not to any of Arabic’s numerous dialects. A horizontal line above the roman letter representing an Arabic vowel indicates a long vowel (ie. ‘ee’ as in ‘beet’) rather than a short one (ie. ‘i’ as in ‘bit’). ء hamzah is never indicated when in intial position.

Note on** hamzah: Occupying the 29th and final row of the

table above, ء hamzah is an integral component of the Arabic writing system. It is, however, not usually properly considered to be an actual letter of the 28-letter Arabic alphabet. The orthographic rules for its written form are complex. See also, ‘Note on alif, alef, and hamzah.’ (appearing at bottom of linked page)

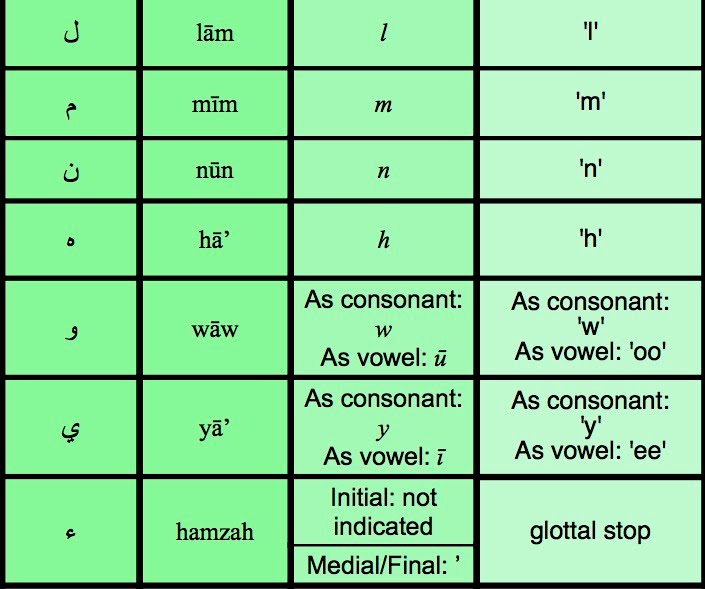

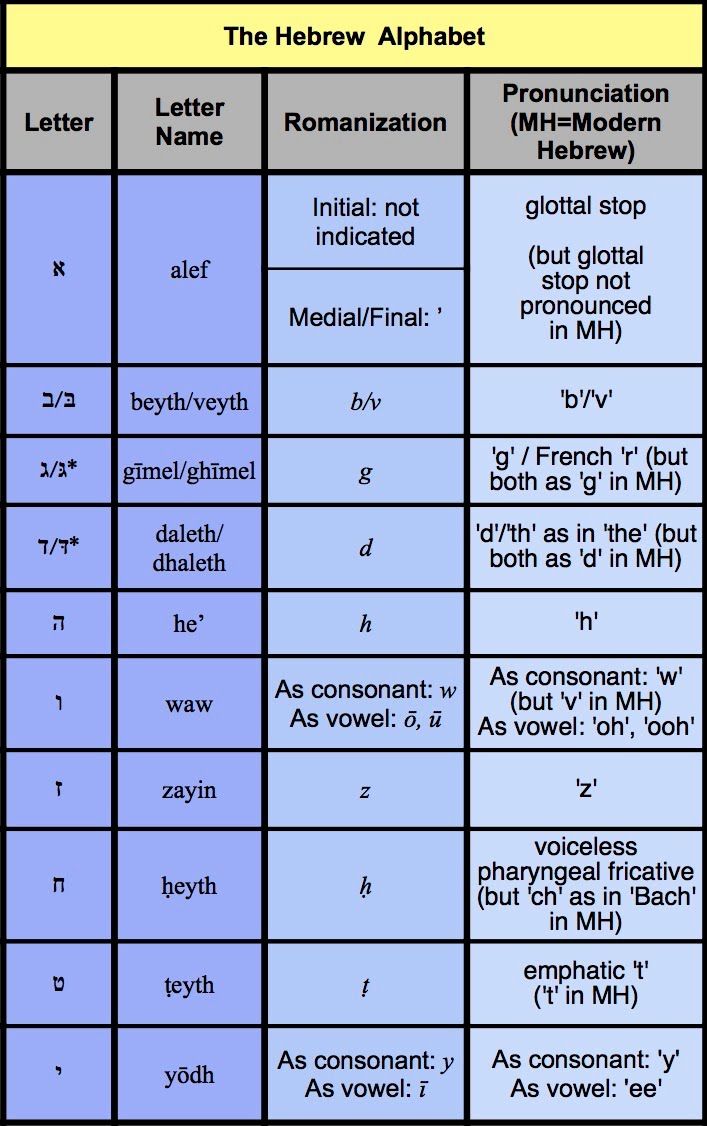

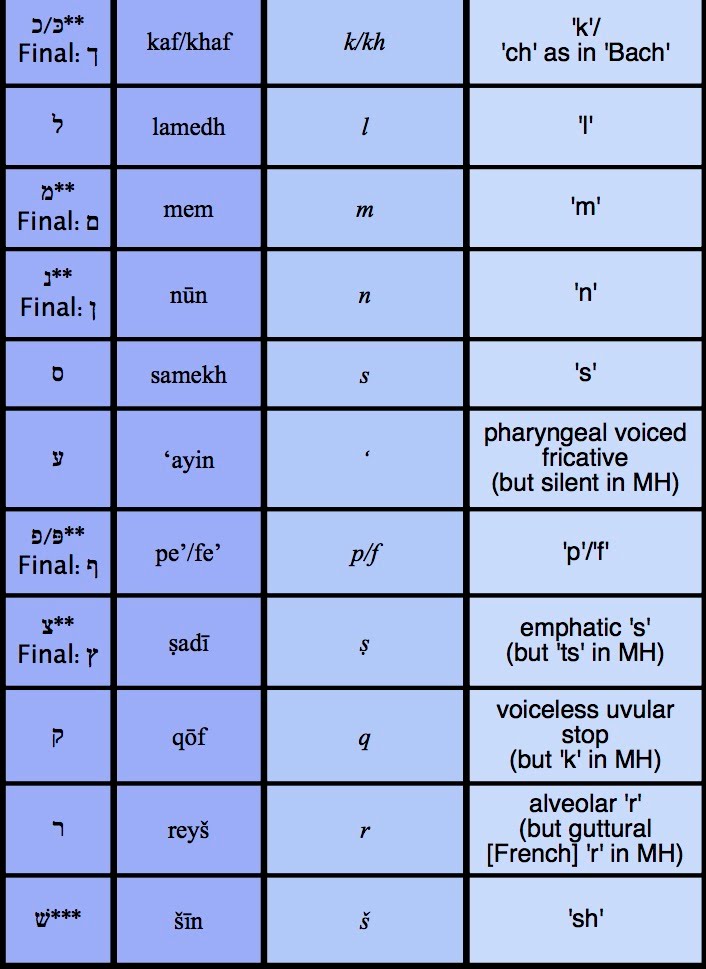

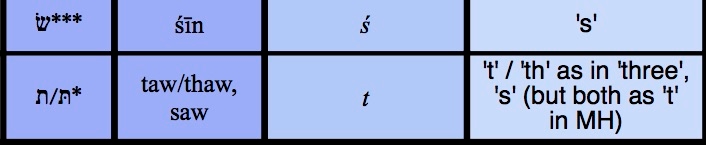

The Hebrew Alphabet

Table 26

*The differentiation between the variants of these letters is not articulated in Modern Hebrew. Only the ‘hard’ versions are used.

**These letters take the indicated final forms when they occur at the end of a word.

***Variants of a single letter of the 22 letter Hebrew alphabet, ש. For the purposes of this chart, each is listed separately in its own row.

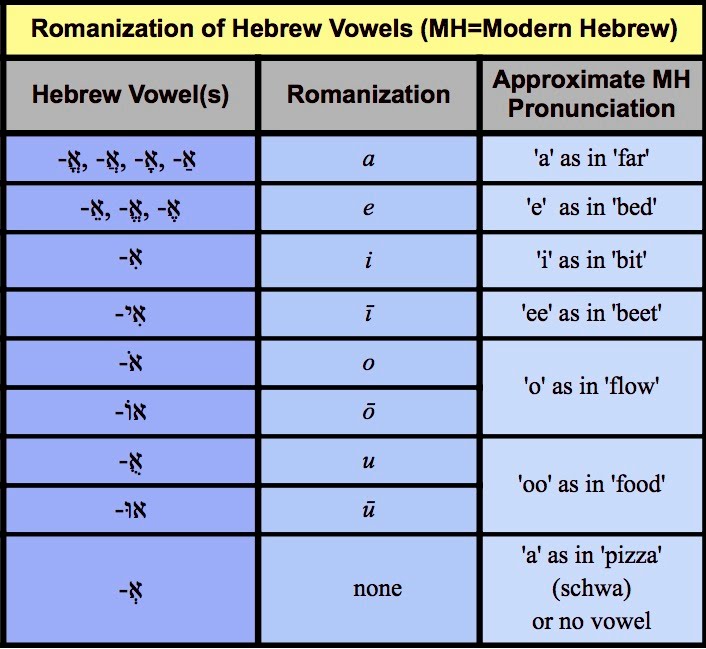

Note on Hebrew Romanization:** In the 3,000 years since Hebrew

began to be recorded as a written language, its pronunciation traditions

have changed to the extent that it is not possible to romanize Hebrew in a way that reflects both its ancient and modern pronunciation. Except in the case of the letter names themselves, we have chosen to romanize the ‘soft’ versions (that is, without dagesh, or center dot) of

the letters בּ b, גּ g, דּ d, כּ k, פּ p, and תּ t to reflect the way they are pronounced in Modern Hebrew. ג is thus romanized as g and not gh; ד

as d and not dh; ת as t and not th. However, we have at the same time chosen to employ subscript dots and other diacritics in order to indicate the several sounds that have lost their original articulation in modern Hebrew. When possible, the same symbols used to transliterate their Arabic corollaries have been chosen. Thus, ṣ is used for צ; ‘ is used for ע; ’ is used for א, except at the beginning of a word, where א ’ is not indicated; ḥ is used to romanize ח, thus making it distinguishable from כ kh; ט ṭ is similarly distinguished from תּ t, as is ק q from כּ k, and שׂ ś from ס s. ו is romanized as w and not as v, thereby distinguishing it from ב v. Hebrew vowels are romanized so as to indicate a total of nine vowels: a, e, i, ī, o, ō, u, ū, and schwa (schwa, and instances of no vowel at all, are indicated simply by absence of romanization), as shown in the table in the next section, in which the letter א represents any consonant.

Romanization of Hebrew Vowels

Table 27

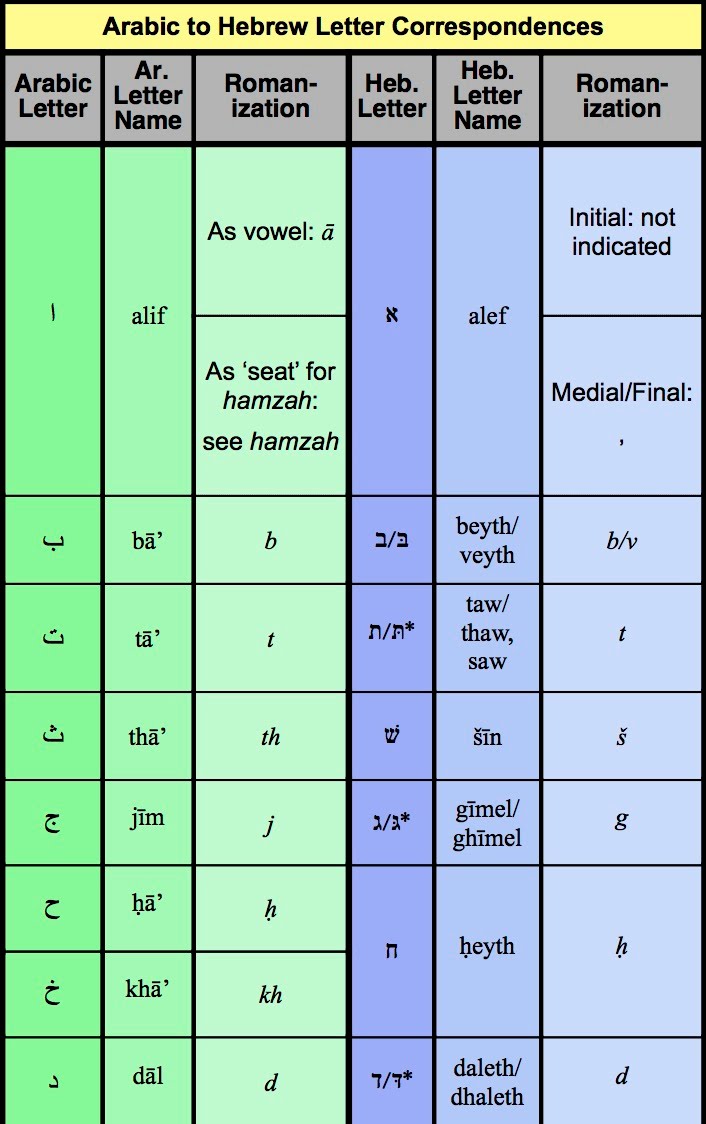

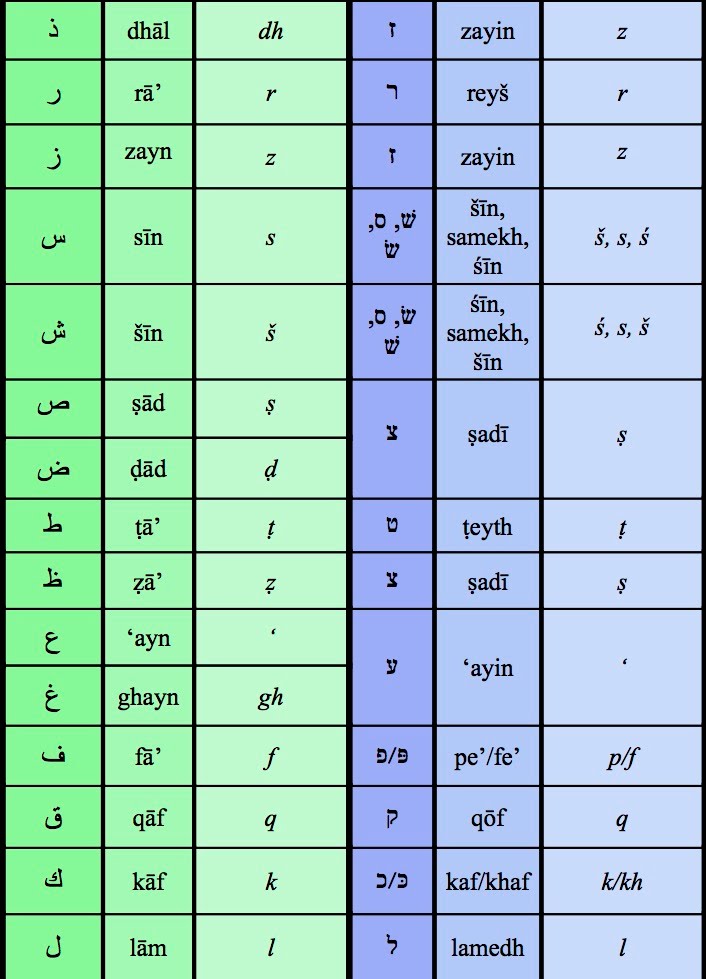

Arabic to Hebrew Correspondences

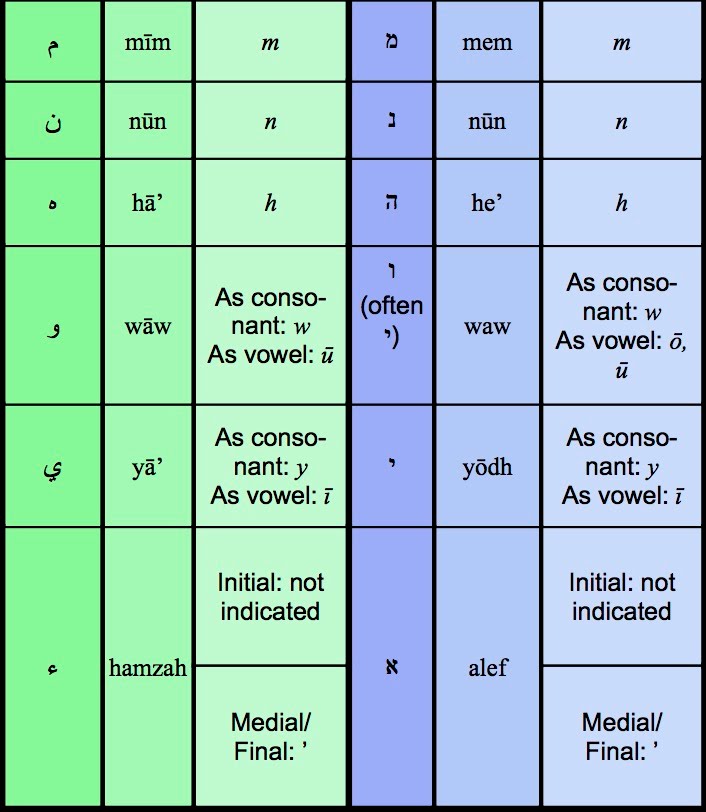

Table 28

*The differentiation between the variants of these letters is not articulated in Modern Hebrew. Only the ‘hard’ versions are used.

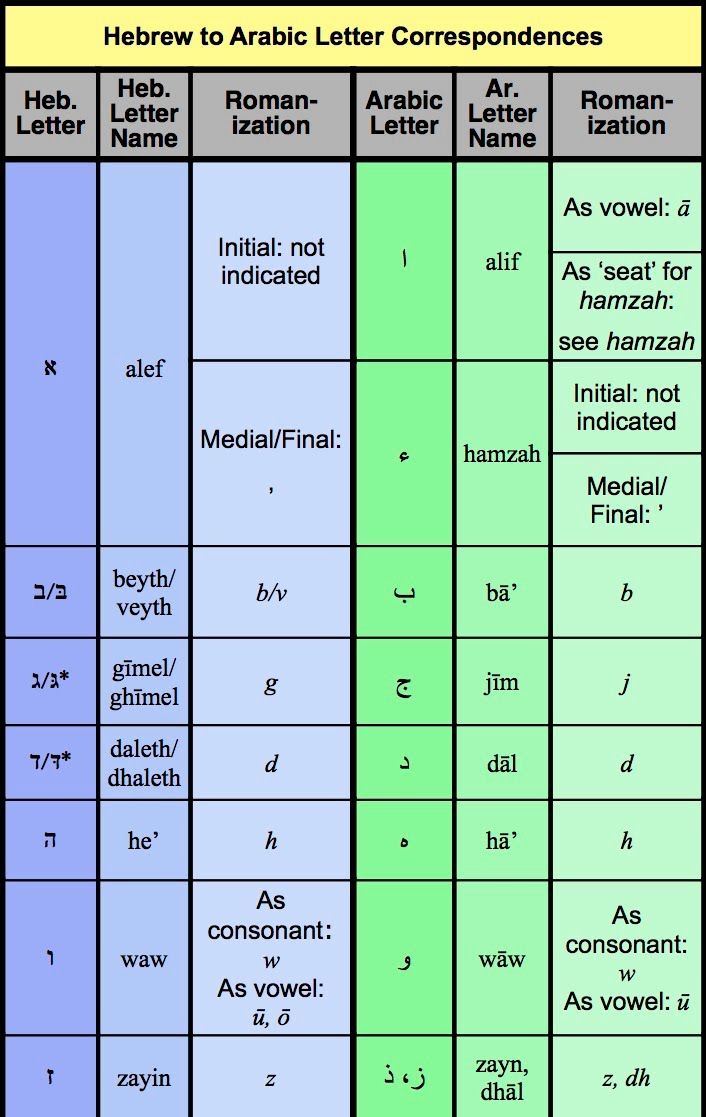

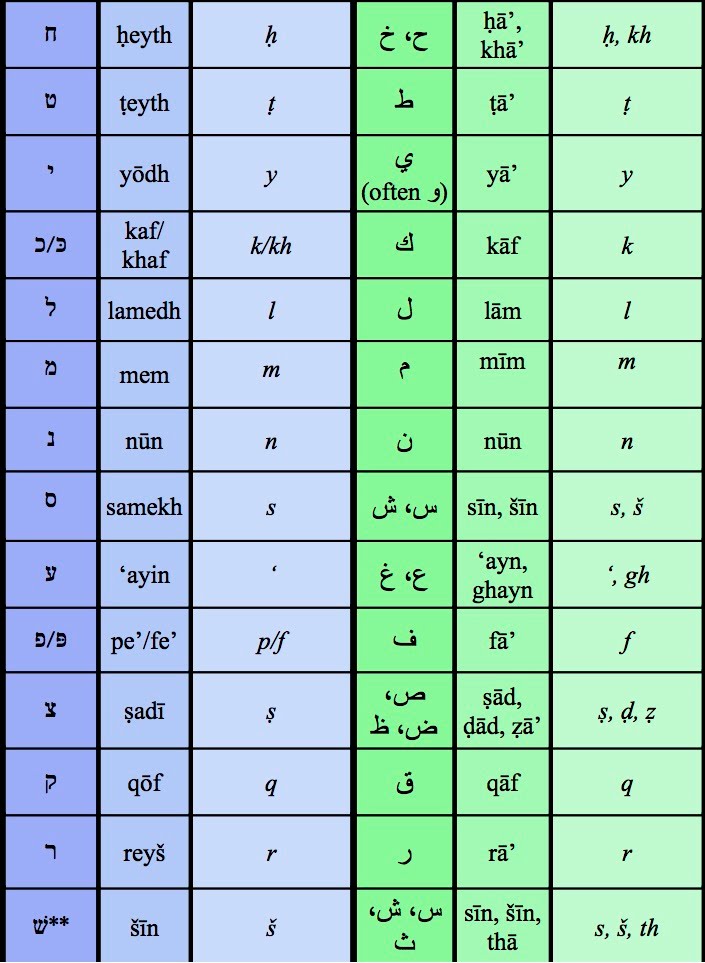

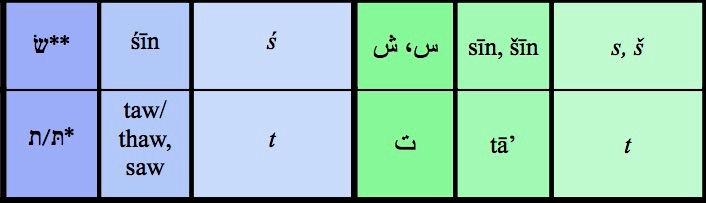

Hebrew to Arabic Correspondences

Table 29

*The differentiation between the variants of these letters is not articulated in Modern Hebrew. Only the ‘hard’ versions are used.

**Variants of a single letter of the 22 letter Hebrew alphabet, ש. Each is listed separately above.

Note on** alef, alif, and hamzah: Hebrew

א alef’s obvious corollary in Arabic is the letter ا alif. Both descendants of a common Semitic letter, each begins its respective alphabet, and each bears a similar name. This correlation between the two letters is reflected in the correspondence presented in Table 28, and in Table 29, above. However, due to written Arabic’s system of orthography, which requires ء hamzah to ‘sit’ upon either ا alif or another Arabic vowel letter when glottal stop is represented, the Arabic correlate of a given א alef will, depending upon the adjacent Arabic vowels, not always ‘sit’ upon ا alif, but rather upon و wāw or (non-pointed) ى yā’. For example: Hebrew רֵאָה re’ah (containing א alef), but Arabic رِئَة ri’ah (containing ء hamzah ‘sitting’ not upon ا alif, but upon ى yā’), both words meaning ‘lung’. ء hamzah may also appear alone, without the ‘support’ of a vowel letter, for example in the Arabic corollary of Hebrew קִשּׁוּא kiššū’, ‘cucumber; zucchini’: قِثَّاء, qiththā’, ‘cucumber’. Neither initial ء hamzah nor initial א alef are indicated in romanization. All words romanized as beginning with a vowel thus contain either initial ء hamzah in the case of Arabic, or initial א alef in the case of Hebrew.

Diagram Hebrew Loses Sounds that are Preserved in Arabic

Hebrew Loses Sounds that are Preserved in Arabic

Links

Semitic Roots Repository is dedicated to documenting and modeling every single aspect of the Semitic languages. It features this wonderful chart: Phonetic Mergers in the Semitic Languages

Abbreviations:

(adj.) = adjective

(agr.) = agriculture

(astr.) = astrology

(B) = Babylonian month name. Used in Hebrew as part of the Jewish ritual calendar. Used in Arabic in Iraq and the Levant.

(BH) = Biblical Hebrew

(Chr.) = Christianity

(f.) = feminine, female

(geol.) = geology

(leg.) = legal

(M) = Maghribi (North African) Arabic

(m.) = masculine, male

(med.) = medicine

(MeH) = Medieval Hebrew

(n.) = noun

(PBH) = Post-Biblical Hebrew

(pl.) = plural

(s.o.) = someone

Notes on the Lexicon: As the word pairs have been brought together with the goal of demonstrating lexical correspondences, at times this has involved presenting only a limited selection from among a given word’s several possible meanings. In most cases, only those that are in agreement across the two languages are presented. It should be understood that meanings presented are by no means exhaustive, and they are not intended as complete and proper dictionary definitions. Meanings have been sourced from the entire corpus of each language’s history. Some of these may, to a greater or lesser degree, be limited to scriptural, medieval, or modern contexts. Words are presented alphabetically, rather than being arranged according to the root letters of which they are composed. All verbs are presented in Arabic and Hebrew in their 3rd person male past tense form, whereas their English meanings are presented in the infinitive. An exception has been made for several words relating to female reproduction, for which feminine forms are used. Internationally used loanwords (e.g.: biology, radio, pizza, etc.) have been avoided, as has Israeli slang originating in Arabic.